Phish set themselves up for a strange engagement in late December 2010: forgoing any larger tour, the band set up two nights in Worcester, Massachusetts’ DCU Center, before a three-night run at Madison Square Garden— to go ring in a larger and more fruitful year for this nation. Suspicions were mostly confirmed: whether or not Worcester was taken by the band as a warm-up to Madison Square Garden mattered little.

The first night was weirdly calm—what I’d expect if, since the Halloween run, the boys haven’t talked or practiced any Phish fodder: Mike’s been busying touring and pressing his latest solo effort on vinyl, and Trey’s been conducting orchestras in New Jersey ever since they closed their three night run in Atlantic City. The first set of the first night held in it some of the strangest spontaneous choices of any band in live performance I’ve ever witnessed: after a pedestrian “Sample In a Jar” and an unremarkable “Funky Bitch,” it was clear that Trey was consulting with Mike, calling the next tune completely on the fly. These suspicions were confirmed as Page and Trey kicked off a Motown/bluesy take on the long-forgotten Velvet Underground cover “Cool It Down.” Why did this happen—a call to “cool it down” on the third song of nothing but a five-night run? Trey was off tempo, and his playing wandered around as they jammed happily along that one chord Lou Reed wrote—a subtle and different treatment than most other jams, if only for its vintage Velvet origin. Later, as Trey called out “Roses are Free,” and the crowd—having amply applied magic droplets from non-Visine bottles to their palms—jumped up and down as if the Ween tune was a winning lottery ticket. I wished the Regal Raisin himself, Gene Ween had been there to help out Trey’s wimpy guitar stylings: not akin to Mark Knopfler’s carefully-chosen licks, and nothing like the crunchy funness that is a Gene Ween solo. Trey was pensive; perhaps the tempo was one notch lower than his cranium’s metronome could handle at that moment. He showed nearly-redeeming, expressive sloppiness through a fast-paced “It’s Ice;” in more fascinating moments, Trey invented new ways to make his axe go dweedle-dweedle-dee way up high on the scale. Special guests that could have reminded how to play his axe would have included Johnny A, the Allman Brothers, and, as requested by the “LA GRANGE” banner that hung from the railing beside the stage. Highlights there were: the guy next to me spoke emphatically about how he’d been “chasing that “Mound” since 1995,” and that the version of “Cavern” was something more than pedestrian. Trey's repeated guitar notes across the verses of "Heavy Things" were barely enjoyable, though wholly appropriate to the vibe. As we all wandered back through the blistering cold winds, talk of the sets’ references to the prior night’s blizzard didn’t add up to any vastly redeeming display of technical accuracy, creativity or humor: Page chose to employ each of his keyboards during a lengthy jam within “Seven Below,” making great use of the variable oscillator adjustment available on his vintage Yamaha synth—but this experimentation was foreign admist the rest of the right hand-piano/left hand-organ work. I shouldn’t have been left wondering: why was “Seven Below” worthy of cool synthy tricks, and we were left to flounder in the same old groove through most of the show? Finest moments included the ultimate and seasonally-appropriate "Farmhouse," treating this ho-hum ballad as tenderly as any poignant Paul Simon torch song; the greatest instrumental work was certainly "What's the Use?," a chord progression that seemed to belong to King Crimson or the like, but was treated with emphatic whole-note respect, some driving and simple psychedelic anthem. "Possum" was interesting, but held no value compared to what I heard of that song this summer.

Night two was made of marked change: "Kill Devil Falls" as an opener wanted to sound like a swampy John Fogerty rock stomp, but couldn't help emulate Great Moments of Last Night. Most important to the quality of the second DCU Center show was Phish's ability to Make Humorous their own material: Mike's grand "My Mind's Got a Mind of its Own" was quick and right and fast, and Trey's goofing around with a recorder that held and played Sarah Palin quotes during "Alaska" helped establish a more relaxed vibe for everyone involved. Because what are the stakes? One may assume a legion of Phish-show attendees are in it for the "beautiful buzz/oh, what a beautiful buzz" (the chorus that ended night one); as literally hundreds gathered to partake before and after the show in those Irresistible Nitrous Balloons, being dispensed on the side streets surrounding the downtown venue, and as Visine bottles were passed down aisles, and careful drops applied to palms and tongues, I came to understand more about how Phish's musical proficiency doesn't especially matter to those on acid, or those racing to consume as much Bud Light as possible from aluminum bottles. What does matter to these folks is Phish's ability to laugh and be creative: Trey's fooling around with Hockey Mom sound clips, and the incredibly apt and useful "She Caught the Katy" that followed were crowd-pleasing on many levels-- and this vibe came to sum in the second night's finest moment: the first set's "Wolfman's Brother," a song I've never especially dug but was thrilled to be a part of on Tuesday night. The night before, during an especially pseudo-tender ballad, I mentioned to a friend that they sounded, without reason, like Murph and the Magic Tones, featuring Mark Knopfler. Four songs in on the second night my Blues Brothers dream came true. Set two began with "Carini," always an interesting and weird non-Zeppelin riff. Songs like "Stealing Time from the Faulty Plan" and "Backwards Down the Number Line" appear fixed in the band's rotation, and add, I guess, an air of Phish 3.0 notoriety to any set. The acapella song "The Birdwatcher," a B-side rarity from years back, was performed for the first time as the first set's closer, and its tight, weird harmonies were intriguing, not grueling or wrong. From "Limb by Limb" to "Harry Hood," night two set two descended into mediocre musicality akin to the Phish cover band playing at the crummy bar up the street (except the aforementioned and stellar "Albuquerque"). The encore may have been the best choice possible for the time and place: dearest Massachusetts teenyboppers, old heads, dreddies, smelly hippies, drunk jocks, wasteoids, "may the good Lord/shine a light on you/make every song your favorite tune/may the good Lord/shine a light on you/warm like the evening sun." Onto the cold streets of Worcester we all spilled out on both nights from the DCU Center, and probably most of us were still seeking such revelation, as the wind made us cold: our faces were made to shine, warmly, to reflect back to the world the beauty we encounter and hear.

Friday, December 31, 2010

Woosterrific Phish: 12/27/10 and 12/28/10

Thursday, December 9, 2010

"Inside Job"

If everything in the Charles Ferguson film "Inside Job" is true, the twenty-first century's collapse of the dollar might, at present and at best, have a spotty and elusive autobiography: one whose last chapter is yet to be written.

Surely Wall Street ran amok amid a new culture of deregulation in the 1980s, as told by Oliver Stone through the phoenix-like character Gordon Gekko across two films; "Inside Job" uses that history as foreground to the current collapse. Worth noting: these are fast and wild days, enough that 'temporary' documentaries, ones that retell a true story that the viewer may act accordingly and in a timely fashion, have come to garner enough attention as to be released and distributed by Sony, through Sony Pictures Classics.

There was a noble and animated attempt to explain the principles at work: subprime and predatory lending, derivatives, among many shots of the New York City skyline and helicopter views of massive office buildings. Surrounding the fall of Lehman Brothers, and its relationship with AIG, many names and faces swirled, from Reagan up to Rham Emmanuel and Obama: they're mostly all in on it, always have been, it seems. Hank Paulson's $700 billion bailout plea to Congress made logical sense, as does the recent international community's call for an end to a culture of bonuses in bank administration.

The film's incrimination of Columbia and Harvard was most striking: interestingly enough, while news of a sizable drug ring on Columbia's campus broke this morning, the other theater was running a flick on Ginsberg's formative trials regarding "Howl," a poem he wrote mostly in his dorm room at Columbia, until he was tossed out. "Inside Job" specifically charges Columbia's economics faculty with violating ethical standards, in preaching one thing in the classroom, and making money on the side doing something different. What's a documentarian to do with such a dead end: an injustice uncovered, an audience left with a massive issue unresolved.

There isn't much characterization of Treasury Secretaries; there isn't anything to laugh at, and almost nothing to be truly entertained by. Leaving the theater with the money in my wallet feeling more brittle and crisp-- as if it may evaporate-- I said a prayer for all the money-lenders, the teachers and the audiences. The Statue of Liberty, not a solution, closes the film, which left me with my hands in the air in disbelief, over shrugging my shoulders.

Surely Wall Street ran amok amid a new culture of deregulation in the 1980s, as told by Oliver Stone through the phoenix-like character Gordon Gekko across two films; "Inside Job" uses that history as foreground to the current collapse. Worth noting: these are fast and wild days, enough that 'temporary' documentaries, ones that retell a true story that the viewer may act accordingly and in a timely fashion, have come to garner enough attention as to be released and distributed by Sony, through Sony Pictures Classics.

There was a noble and animated attempt to explain the principles at work: subprime and predatory lending, derivatives, among many shots of the New York City skyline and helicopter views of massive office buildings. Surrounding the fall of Lehman Brothers, and its relationship with AIG, many names and faces swirled, from Reagan up to Rham Emmanuel and Obama: they're mostly all in on it, always have been, it seems. Hank Paulson's $700 billion bailout plea to Congress made logical sense, as does the recent international community's call for an end to a culture of bonuses in bank administration.

The film's incrimination of Columbia and Harvard was most striking: interestingly enough, while news of a sizable drug ring on Columbia's campus broke this morning, the other theater was running a flick on Ginsberg's formative trials regarding "Howl," a poem he wrote mostly in his dorm room at Columbia, until he was tossed out. "Inside Job" specifically charges Columbia's economics faculty with violating ethical standards, in preaching one thing in the classroom, and making money on the side doing something different. What's a documentarian to do with such a dead end: an injustice uncovered, an audience left with a massive issue unresolved.

There isn't much characterization of Treasury Secretaries; there isn't anything to laugh at, and almost nothing to be truly entertained by. Leaving the theater with the money in my wallet feeling more brittle and crisp-- as if it may evaporate-- I said a prayer for all the money-lenders, the teachers and the audiences. The Statue of Liberty, not a solution, closes the film, which left me with my hands in the air in disbelief, over shrugging my shoulders.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

The Last Gasps of Howard Stern?

If the self-proclaimed King of All Media were to retire, his departure would as quiet and unpublicized of a disappearance from the airwaves as any minor commercial voice-over drone: a human voice grown so familiar suddenly replaced by a human voice of another, as someone new enters the Theater of the Mind. Howard Stern's counting the days left before the termination of his five-year deal at Sirius, and the show has become increasingly nervous entertainment. If Howard were to be planning his descent into production, ending his routine morning drive-time ritual and, essentially, his career, life on the Stern show would look much as it has, and does.

Howard got wistful months ago, inciting a conversation between Fred ("King of Mars") Norris and "Vegetating" newswoman Robin Quivers, as to who really had an outstanding beef with the show's longtime writer, Jackie (The Joke Man) Martling. After Jackie left over a contract dispute, his seat in the studio would come to be filled-- for a time-- by troubled standup Artie Lange. While Artie's problem was heroin, and his formal and informal rehab will likely prohibit any future appearances on this incarnation of the Howard Stern Show, Jackie'd jump at the chance to appear, even for a day. A few months back-- perhaps seeking to give cred to what were his finest hours in radio-- Howard began to shift toward the sentimental, resulting in his deep voice trembling ever-so-slightly, as it has in decades previous over divorces and national tragedy, over the long-awaited in-studio interview with the elderly creator of a female masturbation machine. Still, Howard attends therapy, at last count, four times each week: his drive to provide for his audience helps him maintain his high standard. In the mind of Howard Stern, success is only available to those who fully commit to a task; thus, the show has been ending consistently at 11:00AM, meandering through Robin's news with a humorous and false sense of hurry.

Howard's neurosis may mean he's never going to "retire," only to repackage and market his vast catalog: clips of his famed Channel 9 shows are wildly funny, and not only for their low-production-value, campy, bad-hair qualities. More easily than may first appear, Howard Stern may further descend into weird post-celebrity mental illnesses-- like Brando or Orson Welles-- if his laurels and previous accolades are what he chooses to rest upon. For now, he still has the chance: it's likely none of us will know the fate of his contract until, perhaps on some January morning, the channels on my Sirius reorganize themselves and his persistent presence will be gone.

Howard got wistful months ago, inciting a conversation between Fred ("King of Mars") Norris and "Vegetating" newswoman Robin Quivers, as to who really had an outstanding beef with the show's longtime writer, Jackie (The Joke Man) Martling. After Jackie left over a contract dispute, his seat in the studio would come to be filled-- for a time-- by troubled standup Artie Lange. While Artie's problem was heroin, and his formal and informal rehab will likely prohibit any future appearances on this incarnation of the Howard Stern Show, Jackie'd jump at the chance to appear, even for a day. A few months back-- perhaps seeking to give cred to what were his finest hours in radio-- Howard began to shift toward the sentimental, resulting in his deep voice trembling ever-so-slightly, as it has in decades previous over divorces and national tragedy, over the long-awaited in-studio interview with the elderly creator of a female masturbation machine. Still, Howard attends therapy, at last count, four times each week: his drive to provide for his audience helps him maintain his high standard. In the mind of Howard Stern, success is only available to those who fully commit to a task; thus, the show has been ending consistently at 11:00AM, meandering through Robin's news with a humorous and false sense of hurry.

Howard's neurosis may mean he's never going to "retire," only to repackage and market his vast catalog: clips of his famed Channel 9 shows are wildly funny, and not only for their low-production-value, campy, bad-hair qualities. More easily than may first appear, Howard Stern may further descend into weird post-celebrity mental illnesses-- like Brando or Orson Welles-- if his laurels and previous accolades are what he chooses to rest upon. For now, he still has the chance: it's likely none of us will know the fate of his contract until, perhaps on some January morning, the channels on my Sirius reorganize themselves and his persistent presence will be gone.

Monday, November 29, 2010

Getting Bluesy and Peculiar with John Sebastian

Tupelo Music Hall, White River Junction 11/28/10

What happens to a first-wave pop-rock guru, a Beatles contemporary, who goes on to have his own tie-dyed career, later to proclaim the virtue of the jug band, having penned unprecedented and goofy tunes such as "Rainbows All Over Your Blues?" From beneath some flat stone did crawleth John Sebastian on Sunday night, all the way to Vermont, bringing with him two guitars (an incredible hollow-body Guild), a Fender Jazz Chorus amp, and his own problematic Audix microphone. Former Lovin' Spoonful frontman and songwriter Sebastian wore black and gray, his mop of thin, nearly-white hair kept from his eyes by trademark spectacles: from beneath these came "You Didn't Have to Be So Nice," "Nashville Cats," "Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?," and so many other anthemic themes relegated to oldies radio. Famously, John Sebastian forgot his own lyrics onstage at Woodstock; he forgot no lyrics on this cold night at the Tupelo, but danced around the stage in a novel, professional, entertaining way: one that made the slender, gaining-on-antique audience almost not notice that Sebastian was picking a solo along with the band playing only in his head.

Picking was the main verb, over singing or strumming: Sebastian played the whole show with a thumb pick, stopping once to file his nails, even. In the style of Mississippi John Hurt, Sebastian used his guitar diligently, skillfully-- far more adept and off the cuff than I had imagined. A keen sense of the beat may be Sebastian's biggest strength, as a performer: every song deserved at least a gentle foot tap (including the bluesy set closer "Tap That Thang"), and I don't think anything was in three-quarter time. Through playing a lullaby written for his son, and a few tunes written with David Grisman for a 2007 album, Sebastian had moments of guitar proficiency akin to some of Paul Simon's complex patterns on a fingerboard: the way a few minor key changes in "Daydream" were played blew me away (a song written, interestingly enough, in response to being the Supremes' opening act in 1965, and the influence of a 'straight-8' beat in pop music. Sebastian laughingly admitted "Daydream" sounds nothing like a straight-8 Motown beat).

He has, however, lost some of his vocal range: one bluesy number made me think one of his few career moves left may be to pick up a banjo and go join Tom Waits' growing chorus of vintage wailers... and not only for his voice, but Sebastian picks guitar across mid-20th century genres as fine as just about anybody. Old-school pop-rock-folk supergroups aren't in vogue, but if they were, John Sebastian would serve well as the leader of some new legion of lyrical potential. One of his best tunes, aside from having an unfortunate tagline and title ("Strings of Your Heart"), was written as the theme for a television show about guitars... which was canned before it went to production, Sebastian admitted. Quick wisps of high feedback plagued his storytelling, by no fault of Tupelo's top-notch crew: there were three times that his narratives elicited no reaction from the crowd at all, not even a laugh-- one was something about tuning a guitar, and how someone said "don't tune, ever," and he lifted his guitar tuner and said, "look, see, this is all you need!" It was likely weird babble over any reasonable metaphor; then back to picking something relatively interesting. After dispensing a requisite number of hits, Sebastian moved the crowd through one patternful number after another.

Particularities and peculiar (and faulty?) proprietary gear aside, it was a treat to see John Sebastian: I found his "Cheapo-Cheapo Productions Presents Real Live..." album at a yard sale when I was fifteen, and marveled at his ability to persuade and lead a full audience through the whimsy of the less-than-serious song. After seeing him live in 2010, I might assume how that end of life holds less, if not a different brand, of whimsy: after an introductory John Hurt number, Sebastian reflected on his five summers at a summer camp outside of Keene, New Hampshire, and how he was thrust before a crowd of seven-year-olds and told to entertain them, to make up songs and to get them to sing. Later, in describing how he plays songs for his kids, he reiterated his thesis: aim to entertain children and you'll seldom go wrong.

What happens to a first-wave pop-rock guru, a Beatles contemporary, who goes on to have his own tie-dyed career, later to proclaim the virtue of the jug band, having penned unprecedented and goofy tunes such as "Rainbows All Over Your Blues?" From beneath some flat stone did crawleth John Sebastian on Sunday night, all the way to Vermont, bringing with him two guitars (an incredible hollow-body Guild), a Fender Jazz Chorus amp, and his own problematic Audix microphone. Former Lovin' Spoonful frontman and songwriter Sebastian wore black and gray, his mop of thin, nearly-white hair kept from his eyes by trademark spectacles: from beneath these came "You Didn't Have to Be So Nice," "Nashville Cats," "Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?," and so many other anthemic themes relegated to oldies radio. Famously, John Sebastian forgot his own lyrics onstage at Woodstock; he forgot no lyrics on this cold night at the Tupelo, but danced around the stage in a novel, professional, entertaining way: one that made the slender, gaining-on-antique audience almost not notice that Sebastian was picking a solo along with the band playing only in his head.

Picking was the main verb, over singing or strumming: Sebastian played the whole show with a thumb pick, stopping once to file his nails, even. In the style of Mississippi John Hurt, Sebastian used his guitar diligently, skillfully-- far more adept and off the cuff than I had imagined. A keen sense of the beat may be Sebastian's biggest strength, as a performer: every song deserved at least a gentle foot tap (including the bluesy set closer "Tap That Thang"), and I don't think anything was in three-quarter time. Through playing a lullaby written for his son, and a few tunes written with David Grisman for a 2007 album, Sebastian had moments of guitar proficiency akin to some of Paul Simon's complex patterns on a fingerboard: the way a few minor key changes in "Daydream" were played blew me away (a song written, interestingly enough, in response to being the Supremes' opening act in 1965, and the influence of a 'straight-8' beat in pop music. Sebastian laughingly admitted "Daydream" sounds nothing like a straight-8 Motown beat).

He has, however, lost some of his vocal range: one bluesy number made me think one of his few career moves left may be to pick up a banjo and go join Tom Waits' growing chorus of vintage wailers... and not only for his voice, but Sebastian picks guitar across mid-20th century genres as fine as just about anybody. Old-school pop-rock-folk supergroups aren't in vogue, but if they were, John Sebastian would serve well as the leader of some new legion of lyrical potential. One of his best tunes, aside from having an unfortunate tagline and title ("Strings of Your Heart"), was written as the theme for a television show about guitars... which was canned before it went to production, Sebastian admitted. Quick wisps of high feedback plagued his storytelling, by no fault of Tupelo's top-notch crew: there were three times that his narratives elicited no reaction from the crowd at all, not even a laugh-- one was something about tuning a guitar, and how someone said "don't tune, ever," and he lifted his guitar tuner and said, "look, see, this is all you need!" It was likely weird babble over any reasonable metaphor; then back to picking something relatively interesting. After dispensing a requisite number of hits, Sebastian moved the crowd through one patternful number after another.

Particularities and peculiar (and faulty?) proprietary gear aside, it was a treat to see John Sebastian: I found his "Cheapo-Cheapo Productions Presents Real Live..." album at a yard sale when I was fifteen, and marveled at his ability to persuade and lead a full audience through the whimsy of the less-than-serious song. After seeing him live in 2010, I might assume how that end of life holds less, if not a different brand, of whimsy: after an introductory John Hurt number, Sebastian reflected on his five summers at a summer camp outside of Keene, New Hampshire, and how he was thrust before a crowd of seven-year-olds and told to entertain them, to make up songs and to get them to sing. Later, in describing how he plays songs for his kids, he reiterated his thesis: aim to entertain children and you'll seldom go wrong.

Friday, October 8, 2010

New Ben Folds Album NOT About Ben Folds!

I had all but given up on Ben Folds. I came to expect Ben seeking to treat fans to Ultimate Repackaging of the same handfuls of hits (through symphonies, college acapella groups, etc.), while letting his own new creative work trickle out-- through unfortunately banal collections as "Back to Normal" and "Songs for Silverman." A few chestnuts reside on each, but neither album had more than a few examples of Ben working hard: the words, it seems, MUST be truly personal, for Ben to be able to even think of an appropriate chord structure and melody, matching the similarly-valuable message.

I don't fault Ben for this-- my own songwriting career feels plagued by the same reluctance to 'get into the hard stuff' of life, tending towards the goofy and the general over the personal and confessional. Three divorces, kids, and a big relocation to Australia, and Ben still hadn't achieved a lyrical ability to speak generally, honestly, and without tongue in cheek, about his life-- in the same way that one of his obvious heroes, Randy Newman, achieved in the early 1970s, certainly within his first three albums. I wish Ben would have challenged himself to some different extent over this near-decade of ego: perhaps covering Newman's "It's Money I Love" over arranging "Brick" for perennial symphony, acapella and solo piano engagements. Because the message would have been the same.

This is why his best album was still (until recently, perhaps) the final effort by Ben Folds Five, "The Unauthorized Biography of Reinhold Messner." Running with liberties made of his seizing another's identity (that of the name and photo found on Folds' adolescent fake ID), those songs held an intrinsic connection between words and the music that was somehow more earnest, forthright.

All those days are over now for Ben: with "Lonely Avenue," he's become as empowered as Elton John, and as separate from the meaning of his songs. His Bernie Taupin is Nick Hornsby, and the lyricist and Ben have done a yeoman's job of delineating their relationship, and the evolution of such, via Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, and all manner of New Media. It's all very lovely, and worth your reading.

What this means for this music is that Ben is relieved of half of his duties, and that's not a bad thing. The first song, "A Working Day," is Ben at his best, and most clear, at the helm of everything in the studio: if Stevie Wonder set the bar back in the day, for performing all instruments in the multi-track environment, Ben uses "Lonely Avenue" to explore his own abilities to literally build in his own drum fills, making every choice imaginable-- except the lyrics. That whole collaboration with William Shatner, with Captain Kirk reading his poetry and Ben jamming out doesn't count in this genre-- that was spoken word, and weird performance, and "Lonely Avenue" is seeking (again) the pop song, with attach-yourself-to-'em lyrics.

And those are good, too-- most notably, "Levi Johnston's Blues" and "Claire's Ninth." Whether or not "Lonely Avenue" reaches heights of piano-power-pop set by songs like Elton John/Bernie Taupin's "Tiny Dancer," or even achieves standards set by Ben himself decades ago ("Alice Childress," "Eddie Walker") remains to be seen: I need more listening time. I hope to find the same reasons to pound the dash and sing loud while driving, as found back in the day myself. At the very least: props to Ben for trying something new.

I don't fault Ben for this-- my own songwriting career feels plagued by the same reluctance to 'get into the hard stuff' of life, tending towards the goofy and the general over the personal and confessional. Three divorces, kids, and a big relocation to Australia, and Ben still hadn't achieved a lyrical ability to speak generally, honestly, and without tongue in cheek, about his life-- in the same way that one of his obvious heroes, Randy Newman, achieved in the early 1970s, certainly within his first three albums. I wish Ben would have challenged himself to some different extent over this near-decade of ego: perhaps covering Newman's "It's Money I Love" over arranging "Brick" for perennial symphony, acapella and solo piano engagements. Because the message would have been the same.

This is why his best album was still (until recently, perhaps) the final effort by Ben Folds Five, "The Unauthorized Biography of Reinhold Messner." Running with liberties made of his seizing another's identity (that of the name and photo found on Folds' adolescent fake ID), those songs held an intrinsic connection between words and the music that was somehow more earnest, forthright.

All those days are over now for Ben: with "Lonely Avenue," he's become as empowered as Elton John, and as separate from the meaning of his songs. His Bernie Taupin is Nick Hornsby, and the lyricist and Ben have done a yeoman's job of delineating their relationship, and the evolution of such, via Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, and all manner of New Media. It's all very lovely, and worth your reading.

What this means for this music is that Ben is relieved of half of his duties, and that's not a bad thing. The first song, "A Working Day," is Ben at his best, and most clear, at the helm of everything in the studio: if Stevie Wonder set the bar back in the day, for performing all instruments in the multi-track environment, Ben uses "Lonely Avenue" to explore his own abilities to literally build in his own drum fills, making every choice imaginable-- except the lyrics. That whole collaboration with William Shatner, with Captain Kirk reading his poetry and Ben jamming out doesn't count in this genre-- that was spoken word, and weird performance, and "Lonely Avenue" is seeking (again) the pop song, with attach-yourself-to-'em lyrics.

And those are good, too-- most notably, "Levi Johnston's Blues" and "Claire's Ninth." Whether or not "Lonely Avenue" reaches heights of piano-power-pop set by songs like Elton John/Bernie Taupin's "Tiny Dancer," or even achieves standards set by Ben himself decades ago ("Alice Childress," "Eddie Walker") remains to be seen: I need more listening time. I hope to find the same reasons to pound the dash and sing loud while driving, as found back in the day myself. At the very least: props to Ben for trying something new.

Saturday, October 2, 2010

Gandalf Murphy Opens Tupelo Music Hall!

The new Tupelo Music Hall is not located in Slambovia, but White River Junction-- though Gandalf Murphy and the Slambovian Circus of Dreams was happy to "launch the maiden voyage" of the new small-scale, upscale venue over two easy-ridin' sets, to a sold-out crowd. Frontman Joziah Longo took a poll after the first song, and was surprised to find that half of the crowd were Slambovian virgins. Mentioning their old stomping ground, the defunct Middle Earth Music Hall in Bradford, the band may have been expecting a reunion with crowds from those days: they had prepared songs from their earliest studio albums, to present alongside new material.

This didn't matter, though. Joziah and company have become Masters of their Craft, to the extent that any song, it seemed, was do-able, even the Van Morrison number "She Gives Me Religion," dedicated to an about-to-be-married couple in the fifth row (Joziah noted how this and other "sissy" songs were all too useful on the folk festival scene-- their 'live bootleg' from Falcon Ridge in 2009, among other recordings, was available in the lobby). "We wanted to come up and visit y'all," said Joziah, "but we didn't have a place to play." Until now. By the close of the show, Tink, the band's talented instrumentalist and vocalist, suggested (to the roar of the crowd) the Slambovians return to Tupelo for a Christmas show. They closed the show with one of their best inventions, taken from that holiday catalog: "Angels We Have Heard On High," breaking into a Doors-style "G-L-O-R-I-A" chorus, as triumphant as any other joyful noise I've heard.

Gandalf Murphy's strength lies in their variety: introducing one song as being a mix of Syd Barrett, the Moody Blues and Jose Feliciano, their embrace of post-psychedelic ideals through country, folk and rock idioms makes sense (and, as they'll be traveling to London this fall, money). Many tunes sounded like they were written by a less-formal Tom Petty, or was the result of long consultation with the powerless late pop of Paul McCartney-- "Let Me Roll It" would be an excellent cover for the Circus. Gandalf Murphy stuck to the basics, however, pulling two songs from their recent Dylan tribute album, including a remarkable "Positively 4th Street," a "singalong" for the crowd. This sounded far more like Bob's 1975 Rolling Thunder Review over The Basement Tapes, and though the crowd didn't likely know much more than the line "Johnny's in the basement/mixing up the medicine," lead electric player Shark took the opportunity to shine. Through the show, he wailed away on a number of guitars, never trusting sustained feedback-driven notes over his own noodling choices: his licks were quality, thoughtful, sounding as though they belonged on a mid-1970s Dick's Picks. He used a slide on everything, including his phasered-out electric mandolin. The setlist was fluid; the sitar was onstage, but went unused. At one point I wondered how much Aerosmith Shark knows by heart, while more often I imagined his work in a New Riders of the Purple Sage: hiding out among a Nashville groove, picking away, doing on electric guitar what pedal steels can't.

Tupelo could have made easier opening-night choices; the crew owner Scott Hayward assembled obviously doesn't shy away from challenges in microphonics and amplification. Besides singing, Tink played viola, accordions, a glockenspiel, a baritone uke and a few other interesting instruments. Only a truly proficient sound crew could attenuate the room's spankin' new Meyer M series sound system to adequately differentiate between the massive kick drum (18" at least) and Joziah's habit of pulling bass notes out of the last string on his acoustic, while Shark took the lead. In a heavier song (more Deep Purple, less folk) called "Genius" they teased "Voodoo Chile" and Lennon's "I Am The Walrus," before resorting back to more-typically-structured songs, built of simple, complicating shuffles.

In all, the first show at Tupelo Music Hall in White River Junction may serve as proof positive, confirming suspicions: it really is BYOB, it really is classy enough to welcome all manner of New England concert patrons.And, most importantly, Tupelo's crew won't allow anything to go wrong during a performance. The sound of a Circus is fantastic.

This didn't matter, though. Joziah and company have become Masters of their Craft, to the extent that any song, it seemed, was do-able, even the Van Morrison number "She Gives Me Religion," dedicated to an about-to-be-married couple in the fifth row (Joziah noted how this and other "sissy" songs were all too useful on the folk festival scene-- their 'live bootleg' from Falcon Ridge in 2009, among other recordings, was available in the lobby). "We wanted to come up and visit y'all," said Joziah, "but we didn't have a place to play." Until now. By the close of the show, Tink, the band's talented instrumentalist and vocalist, suggested (to the roar of the crowd) the Slambovians return to Tupelo for a Christmas show. They closed the show with one of their best inventions, taken from that holiday catalog: "Angels We Have Heard On High," breaking into a Doors-style "G-L-O-R-I-A" chorus, as triumphant as any other joyful noise I've heard.

Gandalf Murphy's strength lies in their variety: introducing one song as being a mix of Syd Barrett, the Moody Blues and Jose Feliciano, their embrace of post-psychedelic ideals through country, folk and rock idioms makes sense (and, as they'll be traveling to London this fall, money). Many tunes sounded like they were written by a less-formal Tom Petty, or was the result of long consultation with the powerless late pop of Paul McCartney-- "Let Me Roll It" would be an excellent cover for the Circus. Gandalf Murphy stuck to the basics, however, pulling two songs from their recent Dylan tribute album, including a remarkable "Positively 4th Street," a "singalong" for the crowd. This sounded far more like Bob's 1975 Rolling Thunder Review over The Basement Tapes, and though the crowd didn't likely know much more than the line "Johnny's in the basement/mixing up the medicine," lead electric player Shark took the opportunity to shine. Through the show, he wailed away on a number of guitars, never trusting sustained feedback-driven notes over his own noodling choices: his licks were quality, thoughtful, sounding as though they belonged on a mid-1970s Dick's Picks. He used a slide on everything, including his phasered-out electric mandolin. The setlist was fluid; the sitar was onstage, but went unused. At one point I wondered how much Aerosmith Shark knows by heart, while more often I imagined his work in a New Riders of the Purple Sage: hiding out among a Nashville groove, picking away, doing on electric guitar what pedal steels can't.

Tupelo could have made easier opening-night choices; the crew owner Scott Hayward assembled obviously doesn't shy away from challenges in microphonics and amplification. Besides singing, Tink played viola, accordions, a glockenspiel, a baritone uke and a few other interesting instruments. Only a truly proficient sound crew could attenuate the room's spankin' new Meyer M series sound system to adequately differentiate between the massive kick drum (18" at least) and Joziah's habit of pulling bass notes out of the last string on his acoustic, while Shark took the lead. In a heavier song (more Deep Purple, less folk) called "Genius" they teased "Voodoo Chile" and Lennon's "I Am The Walrus," before resorting back to more-typically-structured songs, built of simple, complicating shuffles.

In all, the first show at Tupelo Music Hall in White River Junction may serve as proof positive, confirming suspicions: it really is BYOB, it really is classy enough to welcome all manner of New England concert patrons.And, most importantly, Tupelo's crew won't allow anything to go wrong during a performance. The sound of a Circus is fantastic.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

What will Phish Be for Halloween?

Fast approaching the smallest Halloween show by Phish since 1994 in Glens Falls, it's a good time to speculate as to what's going to go down in Atlantic City's Boardwalk Hall at the end of next month. Let's recap Phish's Halloween cover album adventures thus far:

1994. The Beatles' White Album.

1995. The Who's Quadrophenia.

1996. The Talking Heads' Remain in Light.

1999. The Velvet Underground's Loaded.

2009. The Rolling Stones' Exile on Main St.

2010 isn't a year to be swayed into esoteric choices: Phish will cover an album whose pop greatness deserves to be idolized, digitized, whose hit singles still exist on more than one Pandora station. That being said, no Bruce Springsteen album is an obvious choice: though it's the Boss' home turf, I suspect, at most, some musical nod to that catalog Saturday night... at best, a "Rosalita" jam. His debut album "Greetings from Asbury Park N.J." is unlike any other Bruce, in that its pop-inflected grooves are more representative of Van Morrison than of the E Street sound: songs like "Spirit in the Night" and "Growin' Up" would move quickly, and give rise to familiar backbeats and new lyrical challenges... but in the earliest days of Phish, it wasn't Springsteen that the boys were listening to, to dig the grooves.

I don't believe it'll be any Grateful Dead, though Mike joined Kruetzmann and Mickey Hart's ensemble at the Higher Ground in Burlington this past weekend: "American Beauty" breaks out harmonies and slow grooves that truly belong to a different era, and certainly a different generation than the one that'll be huddling for warmth in the late October ocean wind in Atlantic City: though Phish deserves to rekindle its own roots by fully exploring "Truckin'" and "Til the Morning Comes" before an audience, "Attics of My Life" is too daunting for this band, for its tempo, harmony and humility.

It also won't be Bob Dylan's "Blonde on Blonde," and not because it wouldn't be a good choice: I don't believe "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" and others contains enough musical structures to satiate a Halloween show cover album. The novelty of "Rainy Day Women" would soon devolve into a crowd of 5,000 feigning respect, as Trey muddies incessant verses of "Visions of Johanna." Dylan is built of lilting repetition; while a setlist from Dylan's 1974 Rolling Thunder Revue would prove this wrong, there isn't one work that would do both Phish and Bob justice. Harmonica and trampoline don't mix.

I want to say it won't be "Thriller" or "Nevermind," for all their pop glory: Trey's unique way to smell like teen spirit would run the risk of being one of the most downloaded mp3s of all time. Let's hope they don't fall prey to those sensibilities (Randy Newman: "It's Money I Love").

MY TWO BEST GUESSES:

"Physical Graffiti" by Led Zeppelin (thanks to Leah!). Fits the requisite length (four sides of vinyl, like every other Halloween pick so far), is from the time period Phish has chosen in the past to emulate, and would help the boys continue to reclaim their pre-eminence, as Keepers of the Jam. Then, I saw this video, of a cover band doing a decent job with the opener, "Custard Pie" and realized: of COURSE this is a logical Phish Halloween choice. While I'd prefer to hear them rip through Zeppelin's fourth album, "Physical Graffiti" is chock full of live Page/Plant staples: Trey gets to show off appropriately, Mike and Fish get to jive in the way they do best, and Page gets to manufacture a string section for "Kashmir." They've done a few Zep covers through the years (haven't we all?), but never a full-out assault on a mammoth work.

My other best guess strikes more at the ideological heart of Phish, over the musical side: Bowie's famous gender-bending 1972 concept album "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" meets most of the criteria for consideration, and adds an important element of psychedelia. Songs like "Lady Stardust" and "Hang Onto Yourself" should have been covered by now by Phish; most of the set could consist of a jam based on "Suffragette City." Besides Bowie being a namesake of one of Trey's finest early fugue-based compositions, there's a weirdness these two parties share that should be embraced: I want to know when and how Mike has 'freaked out in a moonage daydream;' I want to know how Page would deal with the drama of "Rock and Roll Suicide." As much as Phish could represent the adolescent torment at heart in the Who's "Quadrophenia," they may be even more well-versed in covering Bowie's fully-displaced persona album. "There's a starman waiting in the sky/he'd like to get to meet us/but he think's he'd blow our minds"-- these lyrics might as well be found on the upcoming Gordo album, and the man in the dress will emerge from behind the drums, to rally the troops in singing "Lady Stardust:"

all right

the band was all together

all right

the song went on forever

really quite outasight...

1994. The Beatles' White Album.

1995. The Who's Quadrophenia.

1996. The Talking Heads' Remain in Light.

1999. The Velvet Underground's Loaded.

2009. The Rolling Stones' Exile on Main St.

2010 isn't a year to be swayed into esoteric choices: Phish will cover an album whose pop greatness deserves to be idolized, digitized, whose hit singles still exist on more than one Pandora station. That being said, no Bruce Springsteen album is an obvious choice: though it's the Boss' home turf, I suspect, at most, some musical nod to that catalog Saturday night... at best, a "Rosalita" jam. His debut album "Greetings from Asbury Park N.J." is unlike any other Bruce, in that its pop-inflected grooves are more representative of Van Morrison than of the E Street sound: songs like "Spirit in the Night" and "Growin' Up" would move quickly, and give rise to familiar backbeats and new lyrical challenges... but in the earliest days of Phish, it wasn't Springsteen that the boys were listening to, to dig the grooves.

I don't believe it'll be any Grateful Dead, though Mike joined Kruetzmann and Mickey Hart's ensemble at the Higher Ground in Burlington this past weekend: "American Beauty" breaks out harmonies and slow grooves that truly belong to a different era, and certainly a different generation than the one that'll be huddling for warmth in the late October ocean wind in Atlantic City: though Phish deserves to rekindle its own roots by fully exploring "Truckin'" and "Til the Morning Comes" before an audience, "Attics of My Life" is too daunting for this band, for its tempo, harmony and humility.

It also won't be Bob Dylan's "Blonde on Blonde," and not because it wouldn't be a good choice: I don't believe "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands" and others contains enough musical structures to satiate a Halloween show cover album. The novelty of "Rainy Day Women" would soon devolve into a crowd of 5,000 feigning respect, as Trey muddies incessant verses of "Visions of Johanna." Dylan is built of lilting repetition; while a setlist from Dylan's 1974 Rolling Thunder Revue would prove this wrong, there isn't one work that would do both Phish and Bob justice. Harmonica and trampoline don't mix.

I want to say it won't be "Thriller" or "Nevermind," for all their pop glory: Trey's unique way to smell like teen spirit would run the risk of being one of the most downloaded mp3s of all time. Let's hope they don't fall prey to those sensibilities (Randy Newman: "It's Money I Love").

MY TWO BEST GUESSES:

"Physical Graffiti" by Led Zeppelin (thanks to Leah!). Fits the requisite length (four sides of vinyl, like every other Halloween pick so far), is from the time period Phish has chosen in the past to emulate, and would help the boys continue to reclaim their pre-eminence, as Keepers of the Jam. Then, I saw this video, of a cover band doing a decent job with the opener, "Custard Pie" and realized: of COURSE this is a logical Phish Halloween choice. While I'd prefer to hear them rip through Zeppelin's fourth album, "Physical Graffiti" is chock full of live Page/Plant staples: Trey gets to show off appropriately, Mike and Fish get to jive in the way they do best, and Page gets to manufacture a string section for "Kashmir." They've done a few Zep covers through the years (haven't we all?), but never a full-out assault on a mammoth work.

My other best guess strikes more at the ideological heart of Phish, over the musical side: Bowie's famous gender-bending 1972 concept album "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" meets most of the criteria for consideration, and adds an important element of psychedelia. Songs like "Lady Stardust" and "Hang Onto Yourself" should have been covered by now by Phish; most of the set could consist of a jam based on "Suffragette City." Besides Bowie being a namesake of one of Trey's finest early fugue-based compositions, there's a weirdness these two parties share that should be embraced: I want to know when and how Mike has 'freaked out in a moonage daydream;' I want to know how Page would deal with the drama of "Rock and Roll Suicide." As much as Phish could represent the adolescent torment at heart in the Who's "Quadrophenia," they may be even more well-versed in covering Bowie's fully-displaced persona album. "There's a starman waiting in the sky/he'd like to get to meet us/but he think's he'd blow our minds"-- these lyrics might as well be found on the upcoming Gordo album, and the man in the dress will emerge from behind the drums, to rally the troops in singing "Lady Stardust:"

all right

the band was all together

all right

the song went on forever

really quite outasight...

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

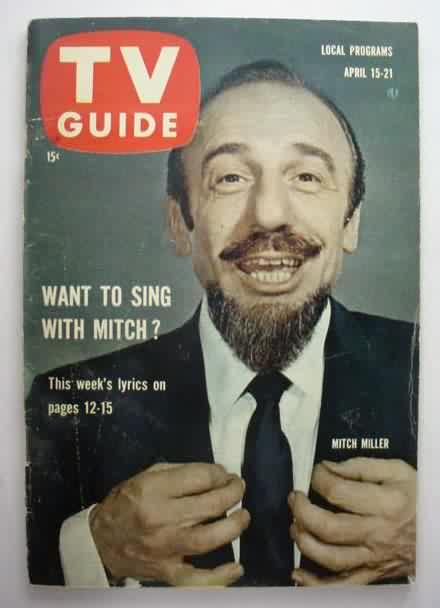

RIP Mitch Miller

Pawing through crates of dusty vinyl in all corners of the country, some records show up often, and are always worth passing over-- and Mitch Miller is responsible for most of them. He is always grinning, smiling as if he were In The Know, beckoning all of us to sing along, to sway to strains of melodies familiar and new. He had our grandparents and parents' eyes following the bouncing ball, shouting "Tzena Tzena Tzena," as the off-key notes were soaked up by the serenity and shag carpeting of the last century's living rooms. Upon his passing, the most appropriate tribute to Mitch Miller may be a full karaoke performance of Rod Stewart's 'American Songbook' album: some tedious and vapid participatory exercise for the ears.

But while his own successful brand (including many records and a television show) sold well, his work as Columbia Records' guru producer is what will go down in musical history. Mitch Miller was mostly responsible for a succession of lucrative, safe, 1950s crooners--Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Frankie Laine, and Johnny Mathis among them. As R & B morphed into rock and roll, and people like Bill Haley and Chuck Berry strummed their guitars increasingly faster, Mitch Miller carried on post-war big-band traditions, perhaps steering the course a bit to the mundane (one critic noted his "perverted brilliance"): think of non-rock-oldies from the 1950s, and it's likely Miller was at the helm of the project, conducting string arrangements through the slow pulse of old pop.

Not many people, in the music business or otherwise, could piss off Frank Sinatra and live to tell about it: Miller did, by making him sing sillier things than one would hear in modern nursery rhymes. Miller is probably why Tony Bennett recorded a highbrow jazz-vocalist album in collaboration with Bill Evans: to prove again that Not All Music is Background. The music was always slow and accessible, a less-ethnic version of Lawrence Welk, but with the same empty-headed happiness at heart: big band bemoans another ballad, and we all have something to which we can fall in and out of love, including the romantically-sustaining horns, the waltzy motion of another slow dance shuffle, or the bellowing of a chorus who, perhaps even in the recording studio, was all made to wear the same cardigan sweaters.

If there had been no Mitch Miller, there may have been less singing in the home in the world-- however contrived and unfamilar such an action may seem-- in the last century. And, had there been no "Sing Along With Mitch" vinyl, ever, perhaps blues would have become rock and roll (what Miller called "musical baby food") faster, or differently. In 1957, Paul Anka was singing "Oh, Diana," Buddy Holly was on American Bandstand, and the Quarrymen were playing their first gigs; Miller, charged by Columbia to pick up the tempo, produced the mildly exciting Marty Robbins hit "A White Sportcoat (and a Pink Carnation)." Sing along to that one!

If the mid-1970s musical GREASE, and its lasting popularity ("High School Musical," etc) means anything, perhaps it marks the moment pop music began to fold over upon itself: repetition of 1950s-style 'rock' riffs were more than permissible, they were encouraged, lucrative. In the 1980s, the synth played the same 1-4-5 progressions that Miller despised; by the 1990s, most pop music was as valid and as poignant as the Gilligan's Island theme song, or the schlock "Beauty School Dropout" from GREASE. By the time GREASE emerged as theater, movie and studio album, Miller's career in home entertainment was all but antique-- and the music that had taken his place was beginning to digest itself again. As much as he despised rock, Miller tried to negotiate a contract with Elvis Presley, but balked at what the Colonel wanted. If Sing-Along-With-GREASE would have made Miller money, he would have done it-- but by then the pop song had been relegated to its own slim genre, and Elvis was already a golden oldie. Miller outlived his medium and his message, and then lived for a long time afterward-- through a stint directing the London Symphony Orchestra in the 80s, through the entire life of Kurt Cobain, all the way to the rise of Lady Gaga, and all the neat sounds we pay for today.

Times are a-changing, though, including inside people's ears. New, soothingly vacant arrangements of standards-- Barry Manilow and Rod Stewart among them-- sell, about as well as anything else these days. Nothing resembles Mitch Miller's "sing along to this one with me" ethic, however. Forgiving his being the Rightful Father of Muzak briefly, Miller is responsible for having established through audio recording a weird kind of community: let's gather at my house and sing along to a record... it even came with a lyric sheet. Had rock and roll not taken the helm of pop, Miller may have been able to convince us to pay .99/download, for access to a bouncing-ball video, helping us remember the words to "Yellow Rose of Texas" and "Heart of My Heart."

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Flaming Lips at Mountain Park, 7/24/10

The Flaming Lips are still on tour, and, like all masters of their craft, they're constantly getting better at what they do: creating community through music. That's not necessarily the thesis that comes to mind during their opener, which still included the band's enterance through their own video screen, as they each emerged on stage from a psychedelic vagina. But as the confetti cannons showered all of us in colored tissue paper; as we kept aloft dozens of massive balloons (and larger balloons filled with small balloons, even), bouncing them off each other's heads; as we all listened and watched, between songs as Wayne Coyne, tireless frontman, sweating profusely, preached an unabashed positivism: we had our collective ears wrapped around some new unity that hadn't existed before.

Part of the fun of all this non-hokey community building was that none of us were really sure where we were. Mountain Park has been open as a concert venue for only a few months, just long enough for the Iron Horse Entertainment Group (also operators of the Calvin Theater, the Iron Horse Brewery, and a few other venues in the western Massachusetts corridor) to work out all the kinks: the pathways are new gravel, the parking lot lighting and roadways are new, the portapotties were clean and well-placed, and, admirably, the vendors didn't appear interested in gouging concert-goers ($1 water $4 fries $5 burger, and a Bud 16oz. aluminum for $7). Once a popular amusement park, the rides and coaster were removed in the late 1980s, and the land was recently purchased by the Iron Horse Group. I was surprised to not see any excavators or bulldozers parked in some corner of the gently-sloped clearing in the woods-- they must have just left-- because the place was close to perfect, in terms of terrain. The Flaming Lips was the largest show at Mountain Park so far: 3,500, with tickets still available at the door. If event organizers wanted to overcrowd this place like they do at Saratoga Performing Arts Center, there would have been 10,000 of us crawling all over the hill, scampering for blanket-space, failing to stretch out on the freshly-unrolled, deep green grass. As it was, we all had space; even if it had been crowded, the sound would have still been amazing. I haven't experienced many truly effective and enjoyable natural ampitheaters, but the placement of the stage was thoughtful, strategic, and well soundchecked.

Wayne Coyne of the Flaming Lips was disoriented in the schedules of the rest of the world, but ever-present in the moment of the show: at one point he mentioned to Steven Drozd their next two nights in New York City, but otherwise he was lost, mentioning twice how he hadn't realized it was Saturday night ("I thought it was Wednesday, or Tuesday, or something"), and appreciating the venue from his place of not-knowing ("I don't know where we are, but this is sure a nice place... whoever's doing this should keep it up").

The day of the week or the location of the venue is less important to the Flaming Lips, as their rock band philosophy continues to manifest in new musical and stage-antic ways: what is more important to Wayne, and the rest of the band, is the message, which is strategically intertwined with the music. At Bonnaroo, I saw them present a 70-minute set to precede their midnight cover of Dark Side of the Moon-- and they rollicked through the confetti, lights, and streamers, punching the crowd with immense bass riffs from their latest album, Embryonic. At Mountain Park, the setting of those new riffs-turned-songs from Embryonic helped support the music in a new way: a song whose main lyric is "when she smiles" (and not the Clouds Taste Metallic ballad) served as the opener, and I imagined Wayne was singing passionately about his wife, even as he climbed upon the shoulders of a man wearing a bear costume; a long, thoughtful song about dreams, though built around many, many gunshot-style paradiddles, was made all the more useful and important given Wayne's introductory pleading ("tell me this is not a dream!"); "See The Leaves" interrupted the mellow, singalong feeling of a section of the second set, being a song about "violence against violence," and featured crafty video montages of animals' teeth, open-jawed and poised for attack.

New material was not overshadowed by older and popular songs, and perhaps this is the Lips' finest achievement; for selfish reasons I don't believe they should remain, as they are in concert, completely ignorant of their masterwork, The Soft Bulletin. Some of the new material sounds like old stuff-- the chorus of the Lips pre-fame "Unconciously Screamin'," for example, may have fit as a bridge into most new jams. "Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots" was the farthest reach back into their catalog; if one ancient song had fit the show, it would have been "Lightning Strikes the Postman." Once, I felt as though I was enduring the strange synth thunder found on the unreleased "The Captain," only to realize I was hearing more Embryonic material.

Some songs were played by a Zeppelin-worthy hard rock outfit; some songs sounded like an un-nervous Pink Floyd cover band who forgot half their gear (plainly, Steven commented to Wayne after a tremendously effective exploratory moment, "that was a nice psychedelic jam, Wayne"); some songs, strummed by Wayne alone and accompanied by Steven on keys/guitar/vocals, sounded more like a John Linnell-John Flansburgh duet than I had ever, ever expected from the Lips (most notably, "I Can Be A Frog"). Wayne was challenged to introduce "The Ya Ya Ya Song," a punchy anti-Bush cheer that, he tried to explain, has not outlived its usefulness.

Surely it has not, because "The Ya Ya Ya Song," as well as much of the newer material, only gave Steven Drozd a playground in which to frolick: a mad musical genius, I had been wowed by his multi-instrumental performance during two sets at Bonnaroo, but one could tell he had a Task At Hand. At Mountain Park, Steven warmed up, playing synthetic strings, electric pianos, and hammering away at his customized double-neck-turned-single-neck twelve string electric guitar. The talkbox became essential during "The Ya Ya Ya Song," and he began to have only more fun with it, singing along with all of his guitar notes. I've heard Trey, Zappa and others espouse the value of singing along with your instrument; I've never seen someone pursue that so accurately, vigorously, musically onstage. And besides, Steven may be taking singing lessons: if the song called for a high E, he shot for it, and seldom missed. Of course, who knows what electronic modifications may lie beneath the layers of road-sign-orange duct tape all over Steven's keyboard and pedal rigs-- but no amount of gear can replace such musicianship. The more harmonies he sang, the more I realized how Steven may be the 21st century's Brian Wilson: Smile.

"In the Morning of the Magicians" was one of the finest live Lips songs I've ever seen, and by far the best song at Mountain Park. This most majestic moment came two-thirds of the way through the evening, as Wayne exclaimed with pride the ability to give love ("to a tree, to an animal, to a person, to a piece of fuckin' food you cook"), you may know that love will always find you, "and so I will give you my love," he said, as he leaned over and gave as much of the crowd a hug as he could-- the first crowd hug I've ever seen. Steven sang all his critical guitar notes as well, and a pair of plastic shakers were critical percussion through the verses. Wayne sang "what is love and what is hate/the calculations error/is to love just a waste?," and the moon rose over the rolling hills of western Massachusetts, and the rain held off, and the video screen showed, in well-timed repitition, the face of a woman dancing in a 1960s esctacy, we were all made to fall in love with life again, with confetti and the crowd around us.

Part of the fun of all this non-hokey community building was that none of us were really sure where we were. Mountain Park has been open as a concert venue for only a few months, just long enough for the Iron Horse Entertainment Group (also operators of the Calvin Theater, the Iron Horse Brewery, and a few other venues in the western Massachusetts corridor) to work out all the kinks: the pathways are new gravel, the parking lot lighting and roadways are new, the portapotties were clean and well-placed, and, admirably, the vendors didn't appear interested in gouging concert-goers ($1 water $4 fries $5 burger, and a Bud 16oz. aluminum for $7). Once a popular amusement park, the rides and coaster were removed in the late 1980s, and the land was recently purchased by the Iron Horse Group. I was surprised to not see any excavators or bulldozers parked in some corner of the gently-sloped clearing in the woods-- they must have just left-- because the place was close to perfect, in terms of terrain. The Flaming Lips was the largest show at Mountain Park so far: 3,500, with tickets still available at the door. If event organizers wanted to overcrowd this place like they do at Saratoga Performing Arts Center, there would have been 10,000 of us crawling all over the hill, scampering for blanket-space, failing to stretch out on the freshly-unrolled, deep green grass. As it was, we all had space; even if it had been crowded, the sound would have still been amazing. I haven't experienced many truly effective and enjoyable natural ampitheaters, but the placement of the stage was thoughtful, strategic, and well soundchecked.

Wayne Coyne of the Flaming Lips was disoriented in the schedules of the rest of the world, but ever-present in the moment of the show: at one point he mentioned to Steven Drozd their next two nights in New York City, but otherwise he was lost, mentioning twice how he hadn't realized it was Saturday night ("I thought it was Wednesday, or Tuesday, or something"), and appreciating the venue from his place of not-knowing ("I don't know where we are, but this is sure a nice place... whoever's doing this should keep it up").

The day of the week or the location of the venue is less important to the Flaming Lips, as their rock band philosophy continues to manifest in new musical and stage-antic ways: what is more important to Wayne, and the rest of the band, is the message, which is strategically intertwined with the music. At Bonnaroo, I saw them present a 70-minute set to precede their midnight cover of Dark Side of the Moon-- and they rollicked through the confetti, lights, and streamers, punching the crowd with immense bass riffs from their latest album, Embryonic. At Mountain Park, the setting of those new riffs-turned-songs from Embryonic helped support the music in a new way: a song whose main lyric is "when she smiles" (and not the Clouds Taste Metallic ballad) served as the opener, and I imagined Wayne was singing passionately about his wife, even as he climbed upon the shoulders of a man wearing a bear costume; a long, thoughtful song about dreams, though built around many, many gunshot-style paradiddles, was made all the more useful and important given Wayne's introductory pleading ("tell me this is not a dream!"); "See The Leaves" interrupted the mellow, singalong feeling of a section of the second set, being a song about "violence against violence," and featured crafty video montages of animals' teeth, open-jawed and poised for attack.

New material was not overshadowed by older and popular songs, and perhaps this is the Lips' finest achievement; for selfish reasons I don't believe they should remain, as they are in concert, completely ignorant of their masterwork, The Soft Bulletin. Some of the new material sounds like old stuff-- the chorus of the Lips pre-fame "Unconciously Screamin'," for example, may have fit as a bridge into most new jams. "Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots" was the farthest reach back into their catalog; if one ancient song had fit the show, it would have been "Lightning Strikes the Postman." Once, I felt as though I was enduring the strange synth thunder found on the unreleased "The Captain," only to realize I was hearing more Embryonic material.

Some songs were played by a Zeppelin-worthy hard rock outfit; some songs sounded like an un-nervous Pink Floyd cover band who forgot half their gear (plainly, Steven commented to Wayne after a tremendously effective exploratory moment, "that was a nice psychedelic jam, Wayne"); some songs, strummed by Wayne alone and accompanied by Steven on keys/guitar/vocals, sounded more like a John Linnell-John Flansburgh duet than I had ever, ever expected from the Lips (most notably, "I Can Be A Frog"). Wayne was challenged to introduce "The Ya Ya Ya Song," a punchy anti-Bush cheer that, he tried to explain, has not outlived its usefulness.

Surely it has not, because "The Ya Ya Ya Song," as well as much of the newer material, only gave Steven Drozd a playground in which to frolick: a mad musical genius, I had been wowed by his multi-instrumental performance during two sets at Bonnaroo, but one could tell he had a Task At Hand. At Mountain Park, Steven warmed up, playing synthetic strings, electric pianos, and hammering away at his customized double-neck-turned-single-neck twelve string electric guitar. The talkbox became essential during "The Ya Ya Ya Song," and he began to have only more fun with it, singing along with all of his guitar notes. I've heard Trey, Zappa and others espouse the value of singing along with your instrument; I've never seen someone pursue that so accurately, vigorously, musically onstage. And besides, Steven may be taking singing lessons: if the song called for a high E, he shot for it, and seldom missed. Of course, who knows what electronic modifications may lie beneath the layers of road-sign-orange duct tape all over Steven's keyboard and pedal rigs-- but no amount of gear can replace such musicianship. The more harmonies he sang, the more I realized how Steven may be the 21st century's Brian Wilson: Smile.

"In the Morning of the Magicians" was one of the finest live Lips songs I've ever seen, and by far the best song at Mountain Park. This most majestic moment came two-thirds of the way through the evening, as Wayne exclaimed with pride the ability to give love ("to a tree, to an animal, to a person, to a piece of fuckin' food you cook"), you may know that love will always find you, "and so I will give you my love," he said, as he leaned over and gave as much of the crowd a hug as he could-- the first crowd hug I've ever seen. Steven sang all his critical guitar notes as well, and a pair of plastic shakers were critical percussion through the verses. Wayne sang "what is love and what is hate/the calculations error/is to love just a waste?," and the moon rose over the rolling hills of western Massachusetts, and the rain held off, and the video screen showed, in well-timed repitition, the face of a woman dancing in a 1960s esctacy, we were all made to fall in love with life again, with confetti and the crowd around us.

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

A Trip to Owl Farm

It was a bright morning in the midwest, and as the Rockies rose before me, and then rose around me, I drove past Woody Creek twice before I found the correct right turn: down into the canyon, off the wide divided highway to Aspen, and onto the Woody Creek main drag. Aspen has always sold its funky charm to its celebrities; never mind that it served Hunter S. Thompson as a home base since he purchased Owl Farm in the early 1960s. Never mind the center of Woody Creek is still a trailer park, a collection of surprisingly shoddy late 1970s metal boxes: one, next to the main drag, had a broken window and an unmowed lawn. Each trailer and lot is owned by the local ski company, to provide affordable housing for resort workers. Otherwise, the land is simply too valuable: "bet you've never seen a half-a-million dollar trailer," joked one of the locals.

Of course, the trailers in Woody Creek are the exception to the rule, as the Big Money can hide away where ever, in the hills beyond the town. Thompson always railed against "the greedheads;" that is, those capitalists for whom no amount of money may suffice. As private planes flew overhead Woody Creek hourly, writer and Thompson's neighbor Mike Cleverly described the day that Ken Lay's wife rolled up to his modest cabin, accompanied by Secret Service: the first news of the collapse of Enron had emerged, and Ken was in town to sell all FOUR of his homes in the Aspen area. Down the road from Thompson's beloved Owl Farm (he once called it his "lighthouse"), the Wiley brothers-- the pair responsible for the Swift-Boat ads that smeared John Kerry-- have a few homes, including one designed by a family member that looks both like a gnome home and fallen-down English cottage. I heard that she sat with an architect and molded the idea out of a lump of clay. To appease the locals, the Wileys donated $600,000 to the local animal shelter.

Other homes are owned by Kevin Costner, Michael Eisner, Kate Hudson, and Jack Nicholson, and others. Hanging out at the cafe and tavern in town, twice I was told that, in Aspen and Woody Creek, "the millionaires have moved out, and the billionaires have moved in."

On Thompson's road, the quiet is priceless: sprinklers sound a wet flutter over manicured lawns, and the squawk of animals rise sporadically from the hills behind the Thompson compound. Hunter's widow, Anita, played with a dog in the side yard; lining the fence that runs across the front of the yard, a woodpile continues to rot. Welded vultures still adorn the gateposts; a welded bat stands on a pole outside the two large picture windows in the front corner of the house.

In town, the Woody Creek Tavern doesn't mention Thompson explicitly, anywhere: photographs, notes, paintings, and years of memories adorn the walls. I met a guy who delivered booze weekly to Owl Farm from Aspen, driving a case of 1.5L Chivas Regal bottles, a case of Groschl flip-top bottles and a case of 1.5L bottles of red wine, "for his secretary.?

February 2005 was an especially dark time in America; though the economy had not yet collapsed, the "greedheads" had already long taken control. Thompson chose to stare down the barrel of a shotgun over enduring Bush's second term; like Plato's "Crito," Thompson had come to abhor the political and social system he had helped to create. On that night, Hunter and his wife had had a fight; she was elsewhere, likely in town; he had been walking with a cane as well, after health problems made him weak. Mike Cleverly wouldn't confirm that Hunter had typed "COUNSELOR" on a lone sheet of paper in his typewriter. Cleverly's own collection of Thompson stories-- The Kitchen Readings-- is available on Amazon; as Hunter's neighbor and friend, he chose his words and stories of Thompson carefully. The definitive biography of Hunter, he said, is being written by Douglas Brinkley, who accepted no pay for his extensive editorial work on two volumes of Thompson's letters.

I passed Cleverly a card with my website address on it, and he chuckled: there is no high-speed internet on his road. "Thompson never had DSL?" "Hunter never had a computer. They'd keep sending them," Cleverly said, "and he'd use them, and then a day later they'd be in the trash." It's important to know that, for all his Gonzo travels, Hunter never surfed the web from his kitchen, never explored the internet from home.

I drove through Aspen ("don't deny yourself," Cleverly told me), leaving behind a dream of Woody Creek, Colorado: Hunter wasn't home, and his widow took no interest in me, holding up a copy of her latest book, "The Gonzo Way," hoping for an autograph. The sun shone across the arid landscape; the sprinklers kept the wealthy lawns wet, and growing.

Of course, the trailers in Woody Creek are the exception to the rule, as the Big Money can hide away where ever, in the hills beyond the town. Thompson always railed against "the greedheads;" that is, those capitalists for whom no amount of money may suffice. As private planes flew overhead Woody Creek hourly, writer and Thompson's neighbor Mike Cleverly described the day that Ken Lay's wife rolled up to his modest cabin, accompanied by Secret Service: the first news of the collapse of Enron had emerged, and Ken was in town to sell all FOUR of his homes in the Aspen area. Down the road from Thompson's beloved Owl Farm (he once called it his "lighthouse"), the Wiley brothers-- the pair responsible for the Swift-Boat ads that smeared John Kerry-- have a few homes, including one designed by a family member that looks both like a gnome home and fallen-down English cottage. I heard that she sat with an architect and molded the idea out of a lump of clay. To appease the locals, the Wileys donated $600,000 to the local animal shelter.

Other homes are owned by Kevin Costner, Michael Eisner, Kate Hudson, and Jack Nicholson, and others. Hanging out at the cafe and tavern in town, twice I was told that, in Aspen and Woody Creek, "the millionaires have moved out, and the billionaires have moved in."

On Thompson's road, the quiet is priceless: sprinklers sound a wet flutter over manicured lawns, and the squawk of animals rise sporadically from the hills behind the Thompson compound. Hunter's widow, Anita, played with a dog in the side yard; lining the fence that runs across the front of the yard, a woodpile continues to rot. Welded vultures still adorn the gateposts; a welded bat stands on a pole outside the two large picture windows in the front corner of the house.

In town, the Woody Creek Tavern doesn't mention Thompson explicitly, anywhere: photographs, notes, paintings, and years of memories adorn the walls. I met a guy who delivered booze weekly to Owl Farm from Aspen, driving a case of 1.5L Chivas Regal bottles, a case of Groschl flip-top bottles and a case of 1.5L bottles of red wine, "for his secretary.?

February 2005 was an especially dark time in America; though the economy had not yet collapsed, the "greedheads" had already long taken control. Thompson chose to stare down the barrel of a shotgun over enduring Bush's second term; like Plato's "Crito," Thompson had come to abhor the political and social system he had helped to create. On that night, Hunter and his wife had had a fight; she was elsewhere, likely in town; he had been walking with a cane as well, after health problems made him weak. Mike Cleverly wouldn't confirm that Hunter had typed "COUNSELOR" on a lone sheet of paper in his typewriter. Cleverly's own collection of Thompson stories-- The Kitchen Readings-- is available on Amazon; as Hunter's neighbor and friend, he chose his words and stories of Thompson carefully. The definitive biography of Hunter, he said, is being written by Douglas Brinkley, who accepted no pay for his extensive editorial work on two volumes of Thompson's letters.

I passed Cleverly a card with my website address on it, and he chuckled: there is no high-speed internet on his road. "Thompson never had DSL?" "Hunter never had a computer. They'd keep sending them," Cleverly said, "and he'd use them, and then a day later they'd be in the trash." It's important to know that, for all his Gonzo travels, Hunter never surfed the web from his kitchen, never explored the internet from home.

I drove through Aspen ("don't deny yourself," Cleverly told me), leaving behind a dream of Woody Creek, Colorado: Hunter wasn't home, and his widow took no interest in me, holding up a copy of her latest book, "The Gonzo Way," hoping for an autograph. The sun shone across the arid landscape; the sprinklers kept the wealthy lawns wet, and growing.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Phish: the Tweezer Shows, 6/18 and 6/19/10

After the second night of Phish's two-night run in Hartford, and the first overcrowded night in the boys' home turf, SPAC, it's safe to assume that one of Vermont's most profitable exports has regained their stature, stage presence and groove: for better or for worse. Before SPAC, I hadn't seen Trey stand dramatically on the stage monitors since the pharmaceutical antics at Coventry in 2004; though a friend and noted Phishtorian declared that she believed "Trey's on something," during a snoozertune at SPAC, there were few other hints that any personal reckless may endanger the Weekapaug Grooves: a missed lick in the first measures of "Reba" and some strange modulation in "Tweezer" can be forgiven-- though not all summer. I think Trey's clean, and substantially more relaxed than during last summer, when they were busy at Fenway, MSG, etc., reopening the tie-dyed scar on the music scene that is Phish.